Investigators call 1982 case ‘chargeable’

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tronc/55JA7AYILFHONOBO5LMPYBNPTI.jpg)

As the 40th anniversary of the 1982 Tylenol murders approaches, investigators are working with prosecutors on a now-or-maybe-never effort to hold a longtime suspect responsible for the poisonings that killed seven people in the Chicago area, the Tribune has learned.

This summer’s meetings mark the latest effort to pin the unsolved killings on James W. Lewis, a former Chicago resident who was convicted years ago of trying to extort $1 million from Johnson & Johnson amid a worldwide panic that arose after the victims took cyanide-laced capsules.

Investigators traveled to the Boston area this week and interviewed Lewis, multiple sources said.

Members of the Illinois State Police, Cook and DuPage state’s attorney’s offices and suburban law enforcement are involved in the effort. Investigators lack physical evidence directly linking Lewis to the crime but describe their findings as a “chargeable, circumstantial case,” according to documents reviewed by the Tribune.

Charges are not thought to be imminent and may not come at all, according to sources. Lewis has long denied being the killer.

Tribune reporters learned of the ongoing law enforcement discussions while conducting a nine-month investigation into the murders. Their findings will be detailed in an investigative series and companion podcast beginning Thursday.

The first installments recount the chaotic 24-hour period on Sept. 29, 1982, in which seven people ingested Tylenol capsules laced with potassium cyanide. The eight-part podcast, “Unsealed: The Tylenol Murders,” is part of a partnership between the Tribune and At Will Media, in association with audiochuck.

Episodes in the newspaper series and podcast will be released online each Thursday through October, with print versions of the series on Sundays.

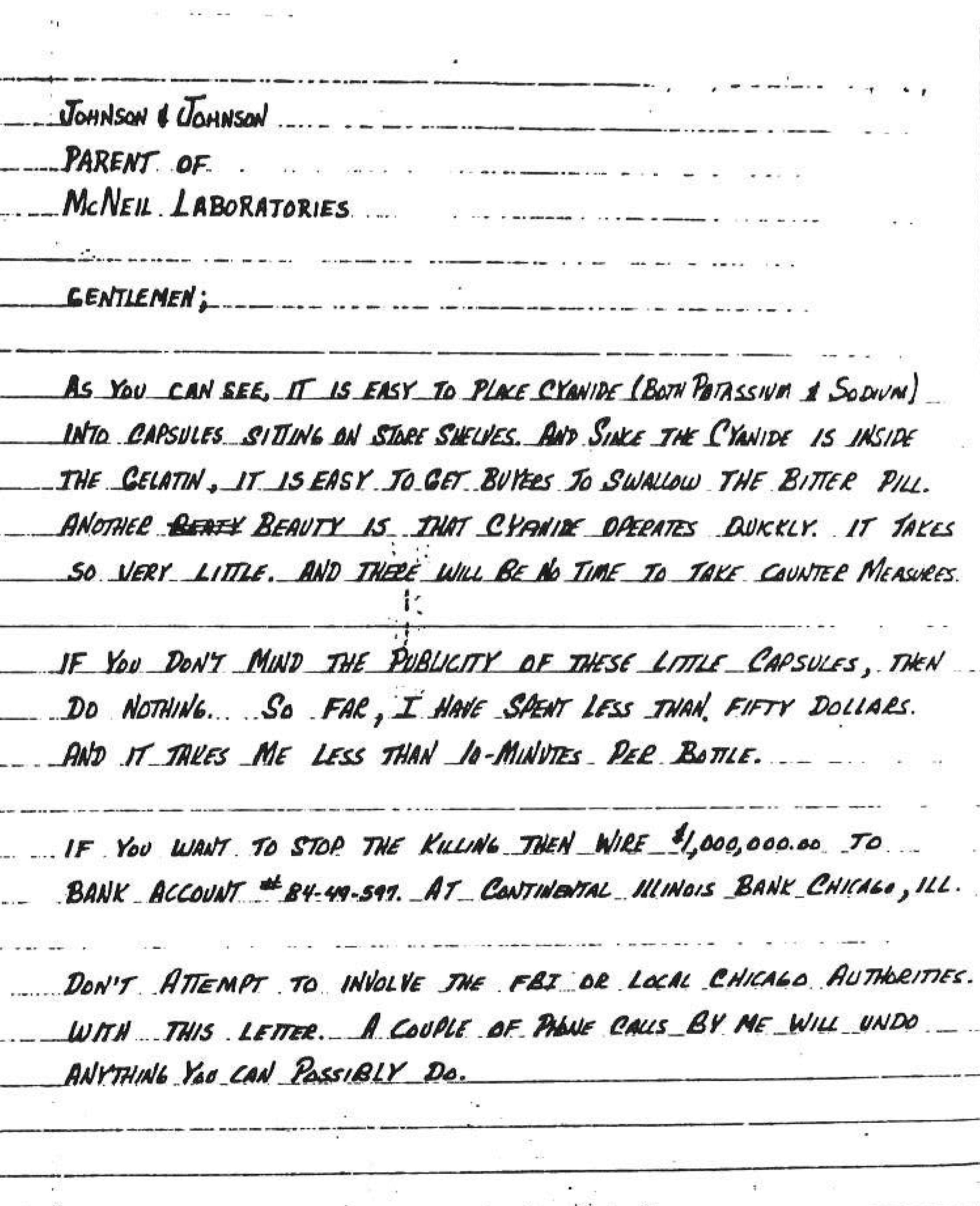

Lewis, 76, has admitted to sending a letter to Tylenol’s parent company, Johnson & Johnson, in the early days of the investigation and demanding payment to “stop the killing.” But he has maintained his innocence regarding the poisonings and various other criminal allegations made against him through the decades.

In a brief conversation with the Tribune last month, Lewis again denied being the Tylenol killer and suggested he has been treated unfairly since he inserted himself into the investigation in 1982.

“Have you been harassed over something for 40 years that you didn’t have anything to do with?” he asked.

A Tribune reporter spoke to Lewis while he was walking near his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He gave no direct response to a question about the ongoing investigation.

Lewis, instead, pointed the finger at Johnson & Johnson and questioned why its corporate scientists were allowed to test bottles that were recalled after the murders. Lewis has long maintained that the company was given too powerful a role in an investigation that centered around its own product.

[ [Part 1] The story of a 40-year-old unsolved case begins with a terrifying medical mystery ]

[ [Part 2] Cyanide-laced Tylenol was the murder weapon. But who was the killer? ]

Records and interviews indicate the company burned the capsules following the testing.

“What have you done on that story about J&J’s destruction of all the evidence?” Lewis asked. “They burned several million capsules.”

A Johnson & Johnson spokesperson did not respond to Tribune questions. In an emailed statement, she noted the tragic case led to important industry safety improvements, such as tamper-resistant packaging.

A former company executive told the Tribune that J&J burned recalled capsules only after testing showed they did not contain cyanide. The company’s scientists found one bottle containing poisoned Tylenol and handed it over to investigators, according to records.

The Tribune’s investigation leading up to the crime’s 40th anniversary included more than 150 interviews in multiple states. Reporters also obtained tens of thousands of pages of documents through records requests, including sealed affidavits and court orders that outline some of law enforcement’s best evidence in the unsolved case.

Among other findings, the Tribune has learned authorities exhumed the body of a second Tylenol suspect, Roger Arnold, in June 2010 and extracted DNA from his remains. Arnold, a former Jewel dockhand and home chemist, became a person of interest after police learned he had been acting erratically and talked in a pub about possessing cyanide. He died in 2008.

According to the sealed exhumation petition, investigators discovered nuclear and mitochondrial DNA upon testing three Extra-Strength Tylenol bottles and the capsules years after the murders. Arnold’s DNA did not match any of the genetic material, sources said.

In fact, so far, none of the forensic testing on the tainted bottles and capsules has shown a link between the poisonings and any suspect, records and sources confirmed. Sources told the Tribune several DNA profiles already had been eliminated from suspicion after testing showed they belonged to people who handled the evidence as part of the investigation.

Also, reporters viewed an FBI video from an elaborate 2007-08 undercover sting operation in which Lewis stated it took him three days to write the extortion letter. Thanks to advances in technology, authorities by 2007 had determined the letter had an Oct. 1, 1982, postmark hidden under layers of ink.

So if Lewis’ statement was accurate, it would mean he began writing the letter before the public knew that tainted Tylenol was killing people. After an FBI agent confronted Lewis with a 1982 calendar and counted back three days, Lewis backed off what he said and stated he must have “faulty memory,” the video shows.

The newspaper also has reviewed a nearly 50-page confidential document outlining law enforcement’s current case, including statements and writings attributed to Lewis over the years that they consider to be incriminating, theories about possible motives, and opinions offered by expert witnesses from the University of Virginia and the National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime.

Among the evidence cited in the document is an old poisoning handbook that authorities say Lewis had in his Kansas City home before he moved to Chicago in 1981. According to the document, experts found fingerprints belonging to Lewis on several pages, including one that explains how much cyanide is needed to kill the average person.

Sources told the Tribune the evidence against Lewis has not changed much since 2010, when investigators as part of a rebooted Tylenol task force obtained fresh samples of his DNA and fingerprints. The FBI also raided his suburban Boston condo and storage locker in early 2009 in the hope of connecting him to the murders.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tronc/LHUAKBX2KRASPCE7D77PERPF4E.jpg)

In summer 2012, at the conclusion of the undercover FBI operation and raid, investigators presented their case against Lewis to Cook and DuPage County prosecutors during a meeting in the FBI’s downtown offices. No charges resulted. Anita Alvarez, the Cook County state’s attorney at the time, left office in late 2016. Robert Berlin is still the state’s attorney in DuPage County.

The police department in Arlington Heights, where three of the victims died, assumed primary responsibility for the Tylenol case in 2013 after the task force dissolved. The department recently told the Tribune the investigation is active and ongoing, with current efforts including DNA testing of decades-old evidence at out-of-state laboratories.

“There are multiple agencies working on this case,” said Arlington Heights police Sgt. Joseph Murphy. “This is not something that we’ve given up on.”

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tronc/GE7R3L3AUVGPVJGLGQ7W6FGVC4.jpg)

A January 2022 meeting with two of Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx’s top criminal investigators did not result in movement in the case, multiple sources said. One of those investigators has since left the office. Berlin and state police Director Brendan Kelly participated in the most recent discussions this summer, with meetings in July and August.

Besides the ongoing forensic testing and traveling to the Boston area, authorities have been preparing for anticipated legal challenges to evidence that stretches back four decades.

Berlin and Foxx’s representatives both acknowledged the case is active and ongoing but declined further comment. Kelly also declined to comment.

Besides the lack of physical evidence connecting Lewis to the murders, authorities have never been able to place him in the Chicago area during the time frame they believe someone put the tainted bottles on store shelves. Lewis had moved from Chicago to New York about three weeks earlier and was living under an assumed name.

[ [Don’t miss] The Tylenol murders: Where were poisoned bottles purchased or discovered? ]

Critics of the investigation have accused authorities of having tunnel vision when it comes to Lewis, but law enforcement sources close to the Tylenol investigation contend they have a good case, albeit one built on circumstantial evidence.

“You go where the evidence takes you,” said Roy Lane Jr., a retired FBI agent who was on the 1982 Tylenol task force and has been involved in later efforts, including the 2007-08 undercover sting. “And the evidence took me to James Lewis. It wasn’t like other avenues were shut off. Other avenues were fully investigated. Other people were fully investigated.”

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tronc/KZNBUU7ULRBSLMMD4BHODG6M3I.jpg)

Lewis spent about 13 years in federal prison for attempted extortion related to the Johnson & Johnson letter and for committing mail fraud in a Kansas City credit card scam in 1981. He was released from prison in October 1995 and then joined his wife in Cambridge, where he remains today.

His other brushes with the law include facing murder charges in Kansas City, Missouri, related to the 1978 death and dismemberment of an elderly man. The case never went to trial; prosecutors dropped charges against Lewis after a judge found that police had violated Lewis’ civil rights and that key evidence was inadmissible.

Also, prosecutors in Massachusetts charged Lewis in 2004 with kidnapping, drugging and raping a neighbor with whom he had an ongoing business dispute. Lewis spent three years in jail, but prosecutors dropped the charges before trial when the victim declined to testify.

[ [Don’t miss] The Tylenol murders: Read our weekly series and listen to the podcast ]

That’s around the time, in 2007, when the FBI launched its undercover investigation.

Robert Grant, who was the special agent-in-charge of the Chicago FBI field office during the rebooted task force, said investigators presented a solid case and, in his opinion, it should be charged while witnesses are still alive to testify.

“Our position was this may be the last, best chance to bring this to public light, but it’s a prosecutor’s decision, not an investigator’s decision,” Grant said in a recent interview. “I felt very bad for the families. I felt very bad for the people who might be at risk. There’s a public interest to (put all the evidence out there), but that’s a prosecutor’s decision.”

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tronc/YBWJZLAPIVBLDG6H354HSIFF3Q.jpg)

Bob Tarasewicz, whose 20-year-old sister, Terri Janus, was among the victims, said his parents mourned the loss of their only daughter for the rest of their lives.

Though he doesn’t have much faith the case will be solved, Tarasewicz said he hopes the attention surrounding the anniversary will “poke the hornets’ nest” and perhaps spark useful leads.

“My feelings are that there’s still someone out there who knows something,” he said.

[ [Don’t miss] The Tylenol murders: 40 years ago, an infamous Chicago-area crime took these 7 lives ]

In addition to Terri Janus, the victims were her 25-year-old husband, Stanley Janus, of Lisle; his brother, Adam Janus, 27, of Arlington Heights; 12-year-old Mary Kellerman of Elk Grove Village; Mary Reiner, 27, of Winfield; Mary McFarland, 31, of Elmhurst, and 35-year-old Paula Prince of Chicago.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tronc/BYJDQWJKH5FX7JC3IXUFQRVVKU.jpg)

Reiner’s daughter Michelle Rosen collaborated with former J&J employee Scott Bartz on a self-published 2012 book called “The Tylenol Mafia: Marketing, Murder and Johnson & Johnson,” which criticized authorities for quickly ruling out the possibility that the tampering occurred in the distribution and repackaging channels.

She also has expressed her firm belief that Lewis isn’t the killer.

“Lewis was convicted of his opportunistic act and spent 12 years in prison for it,” she said in a statement to the Tribune. “I am appalled that they still circle back to him as the possible murderer. This inhibits the investigation and influences the public into believing a false narrative.”

Rosen has sought investigative records for more than a decade, but her efforts have been thwarted by various agencies because the case has never officially been closed. For this anniversary, she renewed calls to release the investigative records so the victims’ families and, by extension, the public can examine the available information.

She isn’t alone in wanting answers.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tronc/4ZZ6LBIPUZDZXHXYF3MIRCU75A.jpg)

Joseph Janus, 71, told the Tribune he watched as his youngest brother and sister-in-law collapsed just hours after his other brother, Adam, had died. All three had swallowed tainted capsules from the same bottle.

“I hope before I die, I see somebody — their face — who did this,” Janus said. “That was the thing my parents wanted to know too, before they went away. … I hope the day comes.”

His daughter, Monica Janus, said her grandparents visited the cemetery nearly every day, setting up lawn chairs at the graves and at times having a picnic just to be near their slain sons.

“And they’d just spend sometimes half the day sitting at the cemetery crying,” she said.

cmgutowski@chicagotribune.com

sstclair@chicagotribune.com

https://www.chicagotribune.com/investigations/ct-tylenol-murders-investigation-new-developments-20220922-kviipga5dfedrf65pwkztgbxjy-htmlstory.html#ed=rss_www.chicagotribune.com/arcio/rss/category/news/ Investigators call 1982 case ‘chargeable’